The Law Is a Ass: Women’s History and the Law @LyndiLamont

September 16, 2014 by Lyndi Lamont in category The Romance Journey by Linda Mclaughlin tagged as divorce, England, history, Linda McLaughlin, marriage, research, women's history“If the law supposes that,” said Mr. Bumble,… “the law is a ass—a idiot. If that’s the eye of the law, the law is a bachelor; and the worst I wish the law is that his eye may be opened by experience—by experience.”

The quote above is generally attributed to Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, published serially 1837-39, per Bartleby though Dickens may have copied it from a 17th century play, Revenge for Honour by George Chapman. (See http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/the-law-is-an-ass.html) Whatever the origin of the phrase, it makes a fair point. (The word ass, of course, refers to a donkey.)

Nineteenth-century women were likely to agree with Mr. Bumble, when one considers the treatment of women under the laws of the period. I covered a bit of this during my recent talk on Herstory at Orange County RWA in August, though women weren’t the only people treated badly by the law. The nineteenth century saw a number of reform movements, from abolitionism to the fight for women’s suffrage. The latter was kicked off in July 19-20, 1848 in Seneca Falls, N.Y. The first two resolutions passed at the convention concern legal matters:

Resolved, That such laws as conflict, in any way, with the true and substantial happiness of woman, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and of no validity; for this is “superior in obligation to any other.

Resolved, That all laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and therefore of no force or authority.

It wasn’t just that women weren’t allowed to vote, though that was a primary focus for reform. For several centuries, a legal practice called coverture was in place in England and the U.S. whereby a woman gave up all rights when she married. Her husband controlled any money or property she brought to the union. Single women, including widows, could own property and enter into contracts without male approval. Thanks to suffragist activism, laws were passed abolishing this practice in the late 19th century.

Current law is confusing enough, but when you’re writing historical romance, the law can be a veritable minefield of potential blunders. Research your time period and location if legal matters play a part in your plot. What kind of legal system was in place at the time? English common law, the Napoleonic Code, church canonical law? In the U.S., laws vary from state to state, but that isn’t always the case in other countries.

British laws were enforced throughout England and Wales, but didn’t necessarily apply to Scotland. For instance, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, the age of consent for marriage was substantially lower in Scotland than the one-and-twenty years required in England, encouraging couples without parental approval to elope across the border. The Gretna Green marriage is common plot device in Regency romances. The 1753 Marriage Act was also the first law to require a formal ceremony. It also required weddings to take place in the morning, hence the wedding breakfast to follow.

Getting out of a marriage was even more difficult. Prior to the mid-19th century when judicial divorce was authorized, it was extremely difficult if not impossible to get a divorce in Britain. In Regency times, one had to petition Parliament for a divorce. Can you imagine having to ask Congress to agree to let someone divorce? Yikes! Even then it was more like a legal separation than a true divorce. Annulments weren’t necessarily easy to obtain either. A law permitting judicial divorce, the Matrimonial Causes Act, finally passed in 1857.

More information on marriage and divorce laws can be found at these sites:

A Brief History of Marriage: Marriage Laws and Women’s Financial Independence by

Karen Offen

Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857”

Linda McLaughlin

0 0 Read moreMorality and Honor: Social Mores in Historical Romance

August 17, 2014 by Linda McLaughlin in category The Romance Journey by Linda Mclaughlin tagged as herstory, historical romance, Linda McLaughlin, morality, research, social mores, writingI was overly ambitious while writing my talk for last Saturday’s OCC/RWA meeting on Herstory: Writing and Researching the Historical Novel, so I’m going to excerpt some of the material I had to omit in my monthly blog post. This month, social mores.

One of the biggest traps historical novelists can fall into is writing historical characters with 21st century mores. And nothing can make the reader want to throw a book across the room quicker. This especially applies to women. The double standard still exists, but it was much greater in previous centuries.

One of the biggest traps historical novelists can fall into is writing historical characters with 21st century mores. And nothing can make the reader want to throw a book across the room quicker. This especially applies to women. The double standard still exists, but it was much greater in previous centuries.War and social unrest have always upset the normal patterns of life, and social mores tend to fall by the wayside during such periods. Still, a historical female character who shows no regard for her reputation isn’t believable unless she’s already a fallen woman and has no reputation to lose. Personally, I don’t necessarily mind a heroine who flaunts society’s rules; I just need to believe that she knows what she is doing and is well motivated in her choices. The woman who doesn’t understand the consequences of her actions strains credibility. Women had a lot more to lose in the not-so-good old days. It’s especially tricky when you have a virginal heroine. People in those days set great store in virginity. But if we’re going to write sensual or erotic historical romance, we need to find a way for our heroines to bypass those restrictions.

Though the concepts may seem rather old-fashioned nowadays, honor and integrity were more important in the past, esp. for men of the upper classes. One of my favorite scenes in Downton Abbey is the one where the Earl of Grantham tries to buy off chauffeur Tom Branson if he will leave Sybil alone. Tom refuses and informs the earl that men in his class are’t the only ones with honor. Point, Tom!

However, morality did tend to vary by class. Upper and middle-class children were taught their manners and the difference between right and wrong while poor kids just tried to survive. In his childrens novel, The Shakespeare Stealer, Gary Blackwood introduces us to Widge, an orphan boy apprenticed to a dishonest clergyman. Dr. Bright teaches Widge a form of shorthand he has developed and then sends the boy to write down other vicar’s sermons. One Sunday, Widge hears Bright deliver one of the sermons he’d copied. At first, Widge doesn’t think too much about it. As he puts it, “As nearly as I could tell, Right was what benefited you, and anything which did you harm was Wrong.”

In George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, the basis for My Fair Lady, Eliza’s father, Alfred P. Doolittle, talks about the undeserving poor and opines on middle class morality.

Morality and honor sometimes require our characters to act against their own best interests, which can be great for conflict.

So how do you know what the social mores of your period were? And how likely were they to be ignored?

See what was going on in the period. As I said, social mores often go out the window in wartime. And history being somewhat cyclical, periods of repression are usually followed by periods of licentiousness, like the English Restoration, a bawdy reaction to the moral restrictions of the preceding Puritan regime of Oliver Cromwell.

Also consider the prevailing religion of the time and location of your book. That will often provide guidance. Moral standards in Puritan New England and Cavalier Virginia during the Colonial period were quite different.

Look for etiquette books for the social niceties. For the Regency period, check out The Mirror of the Graces by A Lady of Distinction, first published in 1811. I have a paperback copy, but it’s available in e-book format format. Google etiquette and your period and you will likely find a lot of choices.

For those who missed the August meeting, I’ve added pages at the Reference Shelf on blog with two of my handouts. Primogeniture still to come.

British Titles: A Brief and Incomplete Guide

Source Books for Historical Writers: A Partial List

Feel free to leave questions and comments below.

Linda McLaughlin / Lyndi Lamont

0 0 Read moreWhat’s In A Name? More Than You Might Think

July 16, 2014 by Linda McLaughlin in category The Romance Journey by Linda Mclaughlin tagged as history, Linda McLaughlin, names, research, writingIn Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare wrote, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” As we soon learned, Juliet’s name was extremely important. She was just any Juliet; she was a Capulet, mortal enemies of Romeo’s Montagu family.

|

|

| copyright 2004 Art Explosion |

As any writer knows, finding the right name for your character is important, esp. the first name. Personal names come with expectations, even the historically improbable ones. Can you imagine Amber St. Claire of Forever Amber as Mary or Nancy? I didn’t think so. I read that Poppy was one of the names Margaret Mitchell considered for her southern belle before she came up with Katie Scarlett O’Hara. Somehow Poppy O’Hara just doesn’t have the same ring to it! Poppy sounds more like a servant girl.

Names have ethnic, class and sometimes religious connotations. Algernon and Reginald, for instance. Not exactly common working men names.

What do Sean, Ian and Ivan all have in common? They are all variants of John, but you wouldn’t name a character Ivan unless he’s from a Slavic country or background. In historical times, the same was true for Sean and Ian. Sean was Irish; Ian Scottish, and historical romances notwithstanding, no upstanding English aristocrat of the past would have allowed his son to be christened Sean or Ian. The priest wouldn’t have allowed it. The parish register would have shown the name as John.

In past centuries, the personal name stock was much smaller than it is now, though not necessarily the same. Prior to the Protestant Reformation, saint names were common. The stricter Protestants rejected many saint names in favor of Biblical names, like Hester and Ezekiel, and even more obscure names. They also invented the so-called virtue names: Faith, Hope, Charity, Prudence, etc.

When choosing names for a historical novel, I look in a book like The New American Dictionary of Baby Names by Leslie Dunkling and William Gosling that gives some historical context for the names. Plus I love the authors’ surnames. I keep thinking it should be Duckling and Gosling, though.

Surnames came into general use in the Middle Ages, and usually come from one of four sources: place of residence, occupation, nickname or patronymics, such as Johnson, Anderson, Davison. In Scotland, Mac at the beginning of a name means son of. In Ireland it’s Mc or O. Patronymics are common to many European countries. The Scandinavian countries also used matronymics, ending in dottir.

When writing an aristocratic character, I look for a less common place name, as the nobility and gentry were usually landed and were likely to take their surname from (or have given it to) the name of their estate. However, the older aristocratic were most likely descended from the Norman invaders and you can find a list of Anglo-Norman names at Wikipedia. Interestingly, Montaigu is one of the names listed. You can also find lists of British titles at Wikipedia, among other online sources. Burke’s Peerage is one of two definitive guides to the aristocracy, but it’s extremely expensive (over $800). You might be able to find an older copy at a local library. The other definitive source on the nobility is DeBrett’s Peerage.

Occupational surnames usually indicate humbler origins. Nearly every village had its baker, blacksmith, cooper, carter, miller and tailer. A few noted exceptions are Stewart, Spencer and Chamberlain, occupational titles of highly placed employees in the royal courts. The royal Stewart ancestors held the title High Steward of Scotland from the 12th century until Robert II became king in the 14th century.

Names based on nicknames, originally called bynames, were used to distinguish two people in a village with the same first name. Bynames include handles like Short and Littlejohn. These were not originally intended as long-term family names but evolved into that.

In the late nineteenth century, Henry Brougham Guppy made a study of farm family surnames as he considered them the most stay-at-home group in the county. In 1890 he published Homes of Family Names in Great Britain in which he categorized names by how common or unusual they were. He found that certain names were “peculiar” to primarily one county. Those are referred to as Guppy’s peculiar names. His book is now available from Project Gutenburg and Google Books.

American surnames come from all around the world and provide a great deal more variety for the novelist than other countries. I became fascinated with names when I was researching my family history. Hunting down my German ancestors was a challenge because the surnames were rarely spelled the same way twice. One of my ancestors started life as Conrad Buchle in Wurttemberg, Germany. A few generations later, his descendents last name was Beighley.

When I started writing around 1988, I collected every name book I could find that had any value for writing historical romance, and boy am I glad I did. Most of them are now out of print, but may be available as used books or in your local public or university library. You’ll find a brief list. I’ll hunt for more. I’m going to be speaking at OCCRWA on writing historical romance in August.

Name Sourcebooks:

American Surnames by Elsdon C. Smith, Genealogical Publishing Company, 2009. http://amzn.com/0806311509

Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, Burke’s Peerage, 107th Edition 2003 http://www.amazon.com/Burkes-Peerage-Baronetage-Knightage-107th/dp/0971196621/

A Dictionary of First Names, Patrick Hanks and Flavia Hodges, 2nd ed., Oxford Paperback Reference, Oxford University Press, 2006. Out of print.

The New American Dictionary of Baby Names, Leslie Dunkling and William Gosling, Signet, 1985, 1991. Better than the average baby name book because it gives some historical context for names. Out of print now.

New Dictionary Of American Family Names by Elsdon C. Smith, Gramercy Publishing, 1988, out of print.

The Oxford Dictionary of English Christian Names by E. G. Withycombe, Oxford University Press; First American edition edition 1947, paperback 1986. Out of print.

The Writer’s Digest Character Naming Source Book, Sherrilyn Kenyon, Writer’s Digest Books, 1994. Available at Amazon.com

Linda McLaughlin

0 0 Read moreAffiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

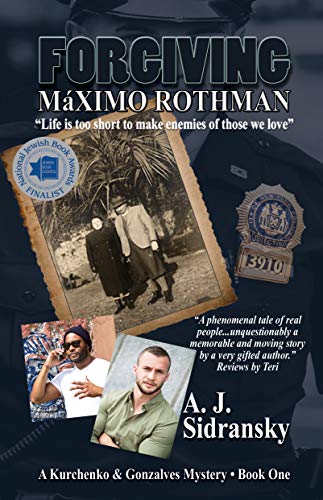

FORGIVING MAXIMO ROTHMAN

Life is too short to make enemies of those we love.

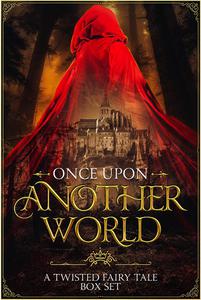

More info →ONCE UPON ANOTHER WORLD: A Twisted Fairy Tale Box Set

Not all fairy tales are as they appear.

More info →SHADOWS AT DAWN

Jax and Mindy have to put aside their overwhelming attraction, but if they live through this, all bets are off…

More info →WHAT MY FRIENDS NEED TO KNOW

Would you break the girl code for love?

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.