Coming into Focus by Dianna Sinovic

January 30, 2021 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic tagged as description, descriptive writing, details, scenes, writingFrom our archives:

The devil is in the details—not only when moving forward with any plan—or with life, but also when working to make a novel, short story, or even narrative nonfiction come to life for the reader.

In the following examples—selected randomly from my bookshelves—the specificity of the details pulls you right into each scene.

The slick black road became narrower, windier, became the single-lane track I remembered from my childhood, became packed earth and knobbly, bone-like flints.— from The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman

His eyes had the bluish gray color of a razor blade, the same polished shine, and as he peered up at me I felt a strange sharpness, almost painful, a cutting sensation, as if his gaze were somehow slicing me open. — from The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

Her clothes can stay behind—her humble pale-print dresses, her floppy hat. The last library book can remain on the table under the sagebrush picture. It can remain there, accumulating fines. — from “The Jack Randa Hotel” in Open Secrets by Alice Munro

With just a few precise details, the authors do more than describe; they weave their tale. The road in Gaiman’s story speaks of the character’s childhood, perhaps a rough one, based on the bumpy flints. The razor-like stare of the man in O’Brien’s scene lets us know the main character has met someone from whom it may not be easy to disengage. And while we know that Munro’s character visits the library, the urgency of her departure makes an overdue book seem trivial.

So, details, yes, but only the right ones. That’s something I struggle with in my writing. As a former journalist, I was taught to focus on the who-what-when-how, so I’m prone to put in too much information.

Earlier this summer I was fortunate to hear Colum McCann speak at the Rutgers Writers Conference in New Jersey. I loved his Let the Great World Spin, and I wasn’t disappointed by what he had to say. In his keynote, he told us of his travels across America when he first arrived in the U.S. from Ireland. All interesting, entertaining stuff, especially when told in his lilting accent, but what really resonated with me was what he called “the beauty of the extreme detail.”

It’s finding the one bit of description to insert in the scene that makes your reader believe that what you’ve described is true. How do you find that one perfect bit? Through your research, of course, whether the research of human experience, through interviews, or by Internet searches.

McCann offered for his example his research into the world of ballet while working on Dancer. After spending hours of time hanging out with a ballet de corps, learning the terminology, the joys and frustrations, the daily life of a dancer, he took his young daughter to see their production of The Nutcracker. He later shared with the dancers his daughter’s hands-down favorite scene: the Waltz of the Snowflakes, with the snow drifting down. It was, the daughter said, magical.

Instead of agreeing with him, the dancers groaned: That scene was their least favorite. The “snow” that fell was swept up after every performance and set aside to let loose at the next one, without filtering out any of the dirt and debris that might have been on the stage. The dancers told McCann that the only thing they could think of when the “snow” began falling was that they would need to wash their hair.

He said that nugget of detail gave him more cred among dancers who read his book than if he had used other, more mundane descriptions of the corps.

I can’t say that I no longer struggle with the details in my WIPs, but they don’t devil me quite as much.

How do you decide which details to include in your writing?

1 0 Read more

Dear Extra Squeeze Team, Is My Blurb Too Long . . . Help?

December 31, 2020 by The Extra Squeeze in category The Extra Squeeze by The Extra Squeeze Team tagged as back cover copy, book blurb, description, The Extra Squeeze Team, writing

Dear Extra Squeeze Team, I am afraid I am telling too much in my book description; it is really long, and I don’t know how to shut up…how do I make it concise?

Robin Blakely

PR/Business Development coach for writers and artists; CEO, Creative Center of America; member, Forbes Coaches Council.

If you think you are telling too much, you probably are. Likely, you are caught up in the literal play-by-play of the work, rather than the essence of the story that makes the reader want to read. One way to make the description shorter and more interesting is to step away from the task completely for a bit. Ask readers of the manuscript to send you their descriptions. Acquire three or four descriptions and blend those descriptions. Try not to get too emotionally caught up in the story of the story. Remember: this is about coaxing readers to read, not writing a book report to prove you know what happened.

H.O. Charles

Cover designer and author of the fantasy series, The Fireblade Array

Start with the pieces you want to keep, so that it makes sense, and strip out everything else. Too much description? Too many adjectives? Look at bestseller summaries and take some inspiration from their structure. They will have had whole teams to work on theirs, so don’t worry if it takes you a while to get it right.

Jenny Jensen

Developmental editor who has worked for twenty plus years with new and established authors of both fiction and non-fiction, traditional and indie.

A good book description works more like a lure than a synopsis. Intricate descriptions of ‘what happens’ is too much tell, so don’t give away the story. Try dangling the promise of a great read by hitting the plot highlights as they happen on your dramatic arc — and then leave it dangling before you hit the denouement.

If you pare it down to just those points that support and move the plot — this could be characters, the problem, the compelling idea — and make the tone fit the story — eerie for horror, soft for romance, brittle for a thriller, punchy for humor — it makes the task more manageable.

A book description is not the condensed version; it’s an opportunity to tantalize and intrigue a reader with what makes your story irresistible.

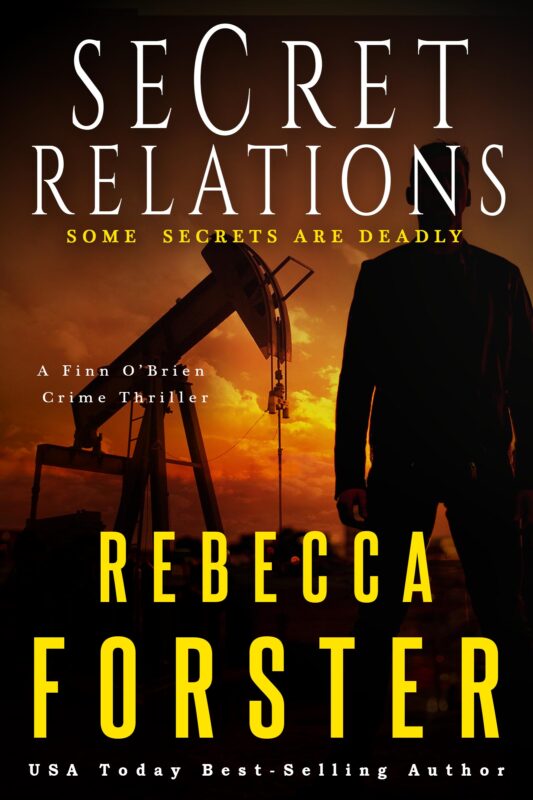

Rebecca Forster

USA Today Bestselling author of 35 books, including the Witness series and the new Finn O’Brien series.

My gut is my favorite writing tool, too. Kudos on recognizing something is wrong. Regarding blurbs, I have taken a lesson from my friends who write scripts and I start with a logline. This is one sentence that lays out the hero, the goal, and the challenge the hero faces.

This is a story about a woman determined to save her family from the ravages of the Civil War no matter what the personal cost.

That is Gone with The Wind in one sentence. Once you have your log line, build on it. Use active words, dramatic words, and draw the reader into the story and stop before you give it away. This is the one piece of writing you should edit, and edit, and edit, and then edit one more time. Blurb writing is a craft to be honed.

Ever wonder what industry professionals think about the issues that can really impact our careers? Each month The Extra Squeeze features a fresh topic related to books and publishing.

Amazon mover and shaker Rebecca Forster and her handpicked team of book professionals offer frank responses from the POV of each of their specialties — Writing, Editing, PR/Biz Development, and Cover Design.

If you have a question for The Extra Squeeze Team, use our handy dandy contact form.

Dear Extra Squeeze Team, What’s an Info Dump, and How Do I Avoid Them?

August 31, 2019 by A Slice of Orange in category The Extra Squeeze by The Extra Squeeze Team tagged as Contests, description, info dumps, Telling, writing

Dear Extra Squeeze Team, I just got back my contest scores and two judges talk about info dumps? What’s an info dump and how do I avoid doing that again?

Rebecca Forster

USA Today Bestselling author of 35 books, including the Witness series and the new Finn O’Brien series.

What I imagine the judge was talking about is the tendency to give the reader every last bit of information about a character or situation, going on for pages and pages without moving the story forward. Remember, you have at least 50,000 and at most 100,000 words with which to create your fictional world. You are not laying tile; you are weaving an intricate tapestry with your words. A bit of discovery here and a reveal there, adds up to a rich story; an information dump is a mud field in which a reader gets bogged down.

Robin Blakely

PR/Business Development coach for writers and artists; CEO, Creative Center of America; member, Forbes Coaches Council.

There’s an old joke that illustrates the act of info dumping. A small child asks her mom: “where do babies come from?” The mom, a passionate teacher, sits down and patiently explains all aspects of biology from conception to birth, mixed with elements of the family’s faith. After ten minutes, the child is overwhelmed with details. She holds up her tiny hand to interrupt her mom’s lengthy explanation and says: “So the part I really want to know is…it’s the hospital, right? Babies come from the hospital?” In writing, don’t be the parent who is trying to share details from the beginning of time with a child who only wants to know a fraction of the info. Be a good curator of info for your readers. If you try to convey a huge quantity of backstory or a massive chunk of background info in one quick dump of detail, you are not doing your job. In real life and in writing, info dumping is overwhelming and distracting. Your knowledge of details may be interesting to you when you are collecting info, but when you share the details, the reader just wants to know the part that directly connects to the story.

Do you have a question for The Extra Squeeze Team?

Use our handy contact form.

Jenny Jensen

Developmental editor who has worked for twenty plus years with new and established authors of both fiction and non-fiction, traditional and indie.

An info dump is a wet blanket, a damper, a downer, a drag. It can consist of a long list of items or events, or an overlong description of a character’s backstory. An info dump can be an overly detailed explanation (often happens with techie things), a showy discourse on the history of a setting, a detailed definition of something only tangentially related to the plot.

Every story has a plot, characters have arcs. The building, then cresting and the resolution of the dramatic arcs are shown in the narrative flow, and that flow is what keeps the reader reading. An unnecessary distraction from the flow – a dump of information that is often tangential, breaks the story and the reader’s rhythm; it’s confusing and (worst of all) often boring. Info dumps have no emotional connection.

An info dump can contain information that is vital to the plot or enriches the story but it is given all at once – it’s a blatant telling dump on the reader – either in narrative or dialog – dampening the story. Every scene has action that is happening in the moment and an info dump is recognizable as narrative that is happening outside the moment of that scene. When Lady Hilda is poised, crystal snow globe in hand, on the landing above Lord Angst it is not the time for a description of Hilda’s life long history of tormenting living creatures with heavy valuable baubles. Just send the damn snow globe crashing down on his bald pate. When Inspector Earnestly digs into the mysterious death he can learn of Hilda’s gruesome past in tidbits and tales from the servants, her friends and family. The reader learns the same information but in a way that emotionally engages them and adds to the dramatic arc.

Info dumps are common and necessary in most drafts. After all, “that’s just you telling yourself the story” (N. Gaiman). When reading over your draft spot those big chunks of information and ask yourself two questions: how much of this info is useful to the story, and how can this info be sprinkled throughout to provide more engagement, emotion and drama? Delete the extraneous stuff even if it is obscure data you would love to share. If it doesn’t move the story forward or improve the tone or feel, it has to go. If it is vital plot info then there absolutely will be a better way to reveal it within the context of appropriate scenes.

Coming into Focus by Dianna Sinovic

August 30, 2019 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic tagged as description, descriptive writing, details, scenes, writing

The devil is in the details—not only when moving forward with any plan—or with life, but also when working to make a novel, short story, or even narrative nonfiction come to life for the reader.

In the following examples—selected randomly from my bookshelves—the specificity of the details pulls you right into each scene.

The slick black road became narrower, windier, became the single-lane track I remembered from my childhood, became packed earth and knobbly, bone-like flints.— from The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman

His eyes had the bluish gray color of a razor blade, the same polished shine, and as he peered up at me I felt a strange sharpness, almost painful, a cutting sensation, as if his gaze were somehow slicing me open. — from The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

Her clothes can stay behind—her humble pale-print dresses, her floppy hat. The last library book can remain on the table under the sagebrush picture. It can remain there, accumulating fines. — from “The Jack Randa Hotel” in Open Secrets by Alice Munro

With just a few precise details, the authors do more than describe; they weave their tale. The road in Gaiman’s story speaks of the character’s childhood, perhaps a rough one, based on the bumpy flints. The razor-like stare of the man in O’Brien’s scene lets us know the main character has met someone from whom it may not be easy to disengage. And while we know that Munro’s character visits the library, the urgency of her departure makes an overdue book seem trivial.

So, details, yes, but only the right ones. That’s something I struggle with in my writing. As a former journalist, I was taught to focus on the who-what-when-how, so I’m prone to put in too much information.

Earlier this summer I was fortunate to hear Colum McCann speak at the Rutgers Writers Conference in New Jersey. I loved his Let the Great World Spin, and I wasn’t disappointed by what he had to say. In his keynote, he told us of his travels across America when he first arrived in the U.S. from Ireland. All interesting, entertaining stuff, especially when told in his lilting accent, but what really resonated with me was what he called “the beauty of the extreme detail.”

It’s finding the one bit of description to insert in the scene that makes your reader believe that what you’ve described is true. How do you find that one perfect bit? Through your research, of course, whether the research of human experience, through interviews, or by Internet searches.

McCann offered for his example his research into the world of ballet while working on Dancer. After spending hours of time hanging out with a ballet de corps, learning the terminology, the joys and frustrations, the daily life of a dancer, he took his young daughter to see their production of The Nutcracker. He later shared with the dancers his daughter’s hands-down favorite scene: the Waltz of the Snowflakes, with the snow drifting down. It was, the daughter said, magical.

Instead of agreeing with him, the dancers groaned: That scene was their least favorite. The “snow” that fell was swept up after every performance and set aside to let loose at the next one, without filtering out any of the dirt and debris that might have been on the stage. The dancers told McCann that the only thing they could think of when the “snow” began falling was that they would need to wash their hair.

He said that nugget of detail gave him more cred among dancers who read his book than if he had used other, more mundane descriptions of the corps.

I can’t say that I no longer struggle with the details in my WIPs, but they don’t devil me quite as much.

How do you decide which details to include in your writing?

2 0 Read moreAffiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

THEIR NIGHT TO REMEMBER

A handsome stranger…With an ulterior motive.

More info →THE OBLIVIOUS BILLIONAIRE

How can you know where you're going if you can't remember where you've been?

More info →SECRET RELATIONS

They're illegal. They're undocumented. They're disappearing.

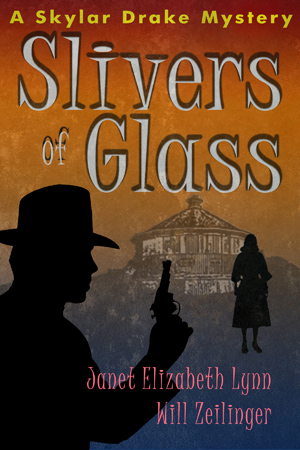

More info →SLIVERS OF GLASS

Southern California 1955: the summer Disneyland opened, but even "The Happiest Place on Earth" couldn't hide the smell of dirty cops, corruption and murder.

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.